Take The Eh? Train

The nights are drawing in. The schools are back. Enthusiastic leaves are starting to tumble, beating the laggards to the ground like eager paratroopers. Plums and apples are bulging, nearly ready to collect. The damsons, far from in distress, are beaming from the bush, harbingers of Christmas joy, when summer warmth will course through veins, somewhat assisted by gin.

Yes; it’s September. Soon the temperatures will plunge, the wind start throwing its weight around, and England will go from not very good summer to entirely convincing winter in a flash. Excellent. Because the season of mists and mellow fruitfulness brings something else: swing.

Next Tuesday my big band returns from its summer break. We’ll turn up to our tiny rehearsal room in a converted customs house and go through the ritual of hi, how was your summer, before settling down to the serious stuff. Peter the band leader will choose a tune, and all seventeen of us will turn as one man (and two women) to ‘the pad’.

This is muso-speak for the pile of music we play, almost a foot tall, most of it dog-eared and scribbled-on. The drum pad has almost a thousand ‘charts’, aka tunes, gathered over decades, all numbered, bulging out of seven folders which were so tattered when I took over the drummer’s ‘chair’ (which is really a stool) I spent two hours with the Sellotape, before admitting defeat and buying some new ones. Before arriving to rehearse I put them all in order, ready for the downbeat. Peter calls out a number, we scrabble to find it, and off we go. Basie or Kenton, Ellington or Miller, they all sit in the pad, eternal classics reduced to numerical anonymity. My Way? 46.Lady is a Tramp? 318. Li’l Darlin? 542.

This numerology is fine when you are the regular drummer, as I am with the Tuesday band; if I can’t find a chart because the pad is out of order, it’s my fault. But when ‘depping’ in a different band, standing in for someone else, it’s like Russian roulette. All the music is there, but not necessarily in the right order, as Eric Morecambe might have said. There’s one band I work with regularly which doesn’t practise, it just does gigs. With no rehearsal. In public. With an audience and everything. The band leader Mick, a brilliant sax player whose introductory patter would make professional comedians fear for their job security, turns round and shouts out two numbers to the band, mid-joke. ‘A hundred and seventy six and eight hundred and fifty’.

‘Was that 850 or 815?” the rhythm section puzzles.

He continues his repartee.

We make an educated guess and pull out two charts, plonking them on the music stand with haste, for time is short, pressure high.

Mick ends the joke, turns to the band, says ‘a three four’ and we’re in. Sight-reading. On a gig. With an audience. (Did I say that?). With crappy copies, too.

This would be hard enough were it not for the issue of girth. I don’t mean the stomach of the lead Alto, but the width of the music. Each chart is five or six pieces of music taped inexpertly together, which are to gravity what sails are to the wind. Some are over a yard wide. As in three feet, not American gardening. I bought a specially broad music stand but even so, each tune starts with half the music teetering off the right hand edge, threatening to tumble to the floor at any minute. To avoid emulating Quasimodo, leaning over and squinting at the cascading crotchets, you have to keep pulling the chart along the music stand, so that eventually the opening page takes on the collapsing role and you can just about glimpse the coda from behind your hi-hats. If you’re lucky.

But you will have instantly spotted the issue here, that drumming per se normally requires the use of quite a lot of the available limbs. As in, all of them. This leaves you somewhat deficient in the music-pulling department. Using your teeth doesn’t really work, and anyway, at my age I can’t focus that close. So one hand stops playing and does the paper transportation, trying not to drop the stick, while the other (and both feet) try to cover what four fourths of you might have previously attempted to achieve. The dexterity required for this is taught at no Conservatoire. When it goes wrong, the entire chart falls off the stand, diving for the floor in a glissando of minims, or indeed a string of pearls. Like buttered toast, it always ends upside down.

That’s when it’s easy. Sometimes the sheets are loose, the sticky tape having perished some time in the Pelopennesian War, when the band got started. Once, we were half way down the last page of a rather fabulous Sammy Nestico number and I thought ‘hmm, this doesn’t sound like it’s going to end any time soon’. I glanced down at the vertiginous pad lying on the floor. Sure enough, another page sat there looking up at me accusingly, one I had entirely missed in the rush to put the music on the stand before Mick’s last punchline. So then you try to pick up the errant last page with your right hand while still playing and … well, you get the general idea.

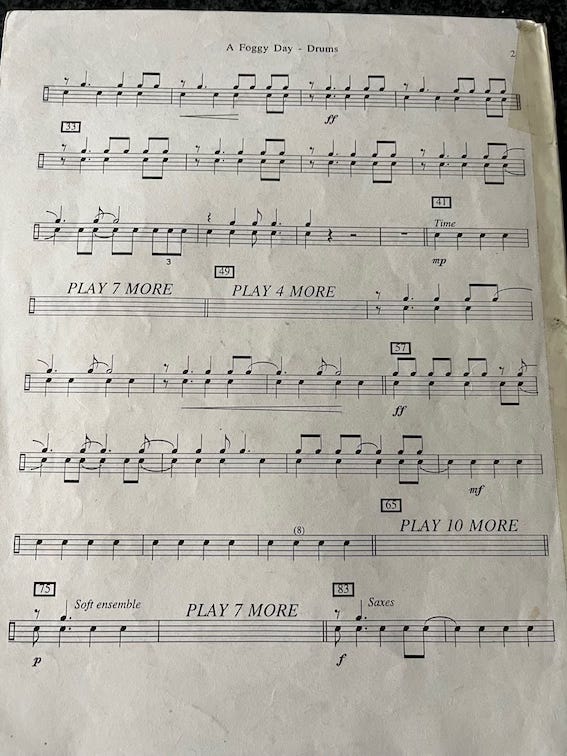

Now I know this must all sound like pointless special pleading, given that it’s only the drums. It’s not like we’re concerned with key changes or anything. We drummers are the people ‘who hang around with musicians’, after all, the butt of jokes. And one look at one of these big band charts might confirm a prejudice that we have it all easy. ‘Twelve bars rhythm’ it will say, followed coquettishly by ‘twelve bars more’. Sometimes the copyist is a sadist, and notates the first bar, then writes ‘play seven more’, which requires mental arithmetic while trying to keep the band in time. It’s instinctive to count up to eight, or twelve, or sixteen; but one plus seven is – well, it adds a certain frisson to the sight-reading, shall we say.

But here’s the thing; what did they even mean by ‘play more’? In an act of flagrant dishonesty, the music, when it is actually notated, always shows even crotchets, also known as quarter notes, but seldom means that. Instead, you have to ‘swing’, which means breaking up the allegedly even notes into a triplet feel: da di da di da, rather than dum dum dum dum dum. So ignore what’s written and work it out for yourself, ok? Good luck. Smile at the audience. Off we go. A two three four.

And then there’s Latin. I don’t mean amo amas amat, but that irresistible stuff from south of the border, down Mexico way. When the chart says ‘Latin’, it’s as helpful as asking for some ‘food’. There’s quite a lot of options available, after all. Does ‘Latin’ mean bossa, or samba, or mambo, or tango, or clave, or rumba, or merengue, or any one of a dozen other air-filled, creamy vibes? And is it even telling the truth? We play a tune called ‘Blue Bossa’ which is not a bossanova at all – it’s a samba. ’12 bars Latin but not the Latin you were expecting starting right now don’t get it wrong happy sight-reading smile at the crowd a two three four’. No UN translator ever faced such interpretive challenges.

But the ultimate conundrum is when the five lines of the stave say ‘play rhythm’ or show anodyne crotchets, and a single line above it teasingly notates something entirely other.

Aha. This means they want you to be good.

The superfluous line is a clue to what the rest of the band is playing; the ‘figures’ or ‘stabs’ which punctuate the tune. When the line shows ‘da dada DAH’, it’s a stab played by one section, maybe the trumpets, while the rest of the band plays the tune. This poses all kinds of questions. I’ll be going ‘ding ding a ling ding a ling’ on a cymbal with my right hand, and ‘cha cha’ on the offbeat with my left on the snare, with both feet playing one and three and two and four, going from right to left. Respectively. Probably. You still with me? All the while, I face a profound and unsettling moral dilemma. What to do about that pesky single line of figures? Should I give the stabs a stab? Just ignore them and stick to the rhythmic knitting?

Here appears the wondrous creativity of big band drumming. Yes, you did read that line correctly. You could treat the figures with complete contempt, resolutely continuing the ding dinga ling and the offbeat and so forth. There are times when what the music most demands is a strong offbeat and no cleverness. Or, you could play the stab with your left hand (snare drum) or right foot (bass drum), while the other limbs keep on keeping on, doing the standard rhythm as well. At the same time. It’s really effective to keep the band together, especially if you anticipate it ever so slightly and play it a fraction early. Everyone sits up straight, and the band feels tight.

But the high art of big band drumming is not just to play the figures, but also to signal their incipient arrival, preparing the way like a percussive John the Baptist. How? By accentuating the upcoming figure with something spontaneous in advance. It’s called a ‘fill’.

So, looking ahead in the chart and backtiming to the trumpet figure, in the tune I am sight-reading which is about to fall on the floor, and just before they play ‘da dada DAH’, I’ll play something completely made up, that very second. Something like ‘bah tiddleypom’. I might even use a paradiddle for this. (Bold, I know).

The result, as you will have instantly realised, goes something like this:

bah tiddlyepom da dada DAH!

And I bet you never read that before.

The real result? Something else, much more magical: groove - that mysterious thing where a whole band moves like a shoal of fish, making your feet tap, bringing a smile to your face.

Conclusion: the drummer, doing four things at once while trying to centre the chart on the music stand, ignores the stabs at his or her peril. Play a fill, and then play the figure too. It’s magic. It makes the band swing.

All of this is done while sight-reading, peering myopically at fading, tattered music that you’ve never seen before and which at any time may fall to the ground. In a gig. With an audience. Yes, an audience. Just imagine.

It’s not as easy as it sounds.

I totally love it. Thank God summer is over.